Look Now for Venus to Cross the Sun, or Wait Another Century

(From “The New York Times”, May 28, 2012)

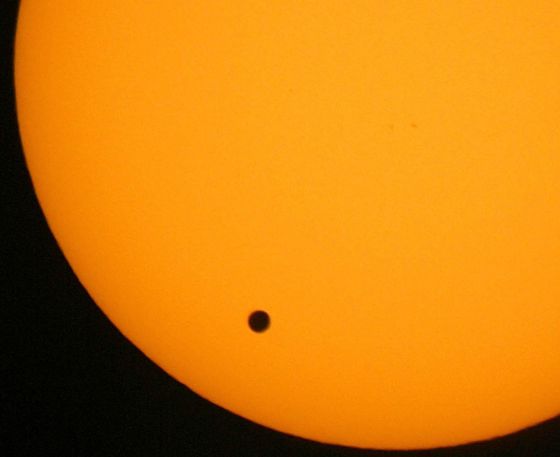

“The next transit of Venus will occur next Tuesday, and will be visible,

at least for a while before sunset, across the United States. In New

York and along the East Coast, the Sun will be low in the sky, requiring

observers to find locations not be obscured by trees or buildings. (A

west-facing window up high in a skyscraper could be a good place to

watch.) The usual precautions about not looking directly at the Sun

apply. Special eclipse viewing glasses can be used, or the image of the

Sun can be projected through a pinhole or binoculars onto a sheet of

paper.

While no longer of great scientific import, as it was to Rittenhouse and

Captain Cook, a Venus transit is still a rare and striking event,

occurring in pairs, eight years apart, about once a century. The last

transit occurred in 2004, and almost no one alive today will be around

for the next one, 105 years from now, on Dec. 11, 2117.

(That one will not be visible at all from most of the United States.

New Yorkers, however, will have a prime viewing spot for the following

transit, on Dec. 8, 2125.)

It was only in 1627 that anyone realized Venus transits occurred at all.

That year, Johannes Kepler, the mathematician and astronomer, published

data about the planetary orbits that predicted that Venus would pass

directly between Earth and the Sun in 1631.

Kepler died in 1630, and it appears no one saw the 1631 transit. (It was

not visible from Europe.) The first recorded observation of a transit

was in 1638, which Kepler had not predicted. Jeremiah Horrocks, an

English astronomer, realized Kepler had made an error in his

calculations.

In 1716, Edmund Halley, the English astronomer remembered for the comet

named after him, proposed how a transit of Venus could be used to figure

out how far the Earth lay from the Sun.

At different locations on Earth, the path of Venus across the Sun would

shift slightly, as would the transit times. With precise measurements,

that would allow someone to triangulate the Sun’s position.

The first attempts came during the 1761 transit, but too few were

successful to calculate the distance. The 1769 effort was bigger and

wider.

In Pennsylvania, Rittenhouse, a noted instrument maker, mathematician,

astronomer and member of the American Philosophical Society, set up an

observatory on his farm to make the transit observations.

The society, the pre-eminent scientific organization in colonial

America, also set up observing stations in the yard next to the

Pennsylvania Statehouse — now Independence Hall — and along the shores

of what is now Delaware.

Rittenhouse’s detailed description of the transit, accompanied by an

exacting diagram, was published in the most prestigious scientific

journal of the time, The Philosophical Transactions, published by the

Royal Society in London.

“That really put these colonial scientists nobody had paid attention to

on the map,” said Sue Ann Prince, director and curator for the American

Philosophical Society’s museum.

The answer that came out of the worldwide 1769 observations was pretty

good: 95 million miles. (Actual answer: 93 million.) “Historically

speaking, it’s the beginning of big international science,” Dr.

Gingerich said.

More expeditions went out to observe the transits in 1874 and 1882, but

already the events were becoming more of a spectacle for the public.

John Philip Sousa wrote a march to celebrate.

With modern technology — radar, in particular — astronomers can now

measure solar system distances much more accurately than was possible

with the transit technique. But some scientists will be making careful

observations of this transit to help with understanding planets around

other stars.

Some of those planets have been discovered by the brief dimming of

starlight as they pass in front of the parent stars. By looking at the

particulars of how the colors change, that could even give clues of the

atmosphere of those distant, unseen planets”.