L´ UKRAINE NE SUPPORTE PLUS...

Link: http://www.lemonde.fr/europe/article/2013/12/26/ukraine-qui-a-decapite-le-lenine_4340166_3214.html

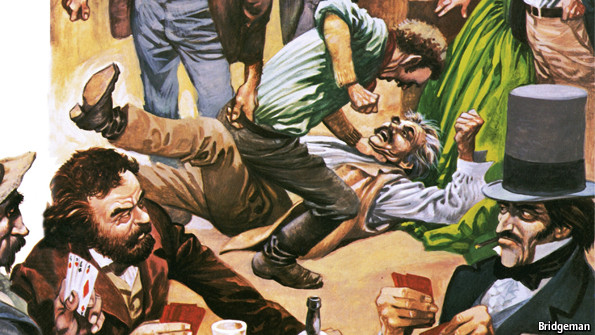

“ARGENTINA CUESTA ABAJO”

|

El

martes 10 de diciembre, nuevamente la Argentina le demostró al mundo

su profunda incapacidad de organizarse políticamente de manera

mínimamente democrática, ciudadana, solidaria y pacífica.

Ese

día el Gobierno argentina emperifollaba el centro de Buenos Aires para

festejar 30 años de Gobierno en “democracia” (casi todos bajo

dirección peronista). La presidenta Cristina Fernández, a pesar de que

ha reducido en forma tajante su exposición pública, tenía ya planeado

pronunciar un discurso en Casa Rosada. Formaba parte de los festejos un

concierto al aire libre con la actuación de grandes artistas locales

(de corte “nacional y popular”, faltaba más) para que la población

notara el profundo apego del gobierno peronista para con la democracia.

En

un acto insólito, el gobierno había previsto la invitación de los

cuatro expresidentes –(Carlos Menem, Fernando De la Rúa, Adolfo

Rodríguez Saá, Eduardo Duhalde y a la familia de Raúl Alfonsín)- que

estuvieron al mando del país durante el período “democrático”. Con la

excepción de De la Rúa y Alfonsín, los otros fueron todos conspiradores

conspicuos contra sus más diversos correligionarios peronistas por lo

que, programar una serie de ceremonias en la que se pretendía poner en

evidencia los supuestos valores de continuidad institucional, civilismo

y solidaridad nacional lindaba entre el mal gusto o la tomadura de

pelo.

Pero

hay veces que la historia, siempre partera de imprevistos, se encarga

de poner las cosas en su sitio. Los años de corrupción oficial y

societal, los ataques sistemáticos a distintos sectores de la sociedad,

el mandoneo rutinario sobre la población y la profunda vocación

anti-democrática que, en realidad, reinó durante todo el período

“festejado” (quedan obviamente excluidos De la Rúa y Alfonsín de este

diagnóstico) repentinamente mostraron sus frutos.

El

acto se transformó radicalmente. Desde algunos días antes, los saqueos

estaban en vías de generalizarse en varias de las provincias del país,

mientras que la “nomenklatura” kirchnerista se aprestaba a jugar a la

fiesta de “la democracia”. En un municipio cercano a la ciudad de

Buenos Aires, el supermercado de un integrante de la comunidad china

fue asaltado por las turbas de “piqueteros”, incendiado el local y

muerto el propietario que pretendía defender algo llamado “derecho de

propiedad”.

Mientras

tanto, en la ciudad de Córdoba, ante el retiro y acuartelamiento

durante 35 horas de la policía de la provincia por sus reclamaciones

salariales no satisfechas, centenares y centenares de locales de todo

tipo fueron vaciados y destruidos. Casi simultáneamente en la provincia

de Entre Ríos se repetían las escenas de Córdoba en Concordia. Lo de

Córdoba en particular fue el doble disparador para dos fenómenos que se

dieron en paralelo. Por un lado, ante el aumento de urgencia otorgado a

la policía de la Provincia, el reclamo policial se generalizó. En más

de una docena de provincias del país los reclamos policiales se

dispararon. El gobierno nacional y los provinciales cedieron, más o

menos rápidamente, a aumentos demenciales e impagables. En el interim,

mientras se buscaban arreglos con las policías, el caos, el saqueo de

locales y el ejercicio de la violencia más disparatada se extendió por

buena parte de la Argentina causando, en el momento que se escribe esta

nota editorial, ya once muertos, un número indeterminados de heridos y

daños de montos difíciles de calcular ya que se calculan en unos 1900

los comercios atacados, saqueados y destruidos.

Alcanza

con ver las tomas televisivas para advertir que los saqueos tienen una

relación muy lejana con una hipotética situación de pobreza de

aquellos sectores de la población transformados en “saqueadores”. Son

muy variados los orígenes sociales de los argentinos que participan en

los saqueos que se han ido extendiendo, finalmente, a lo largo de 20

provincias del territorio y que nadie sabe si han realmente concluido.

En los últimos días, el despliegue de la Gendarmería para proteger todo

tipo de comercios ha enlentecido en algo el contagio de los saqueos.

A

pesar de los análisis edificantes de los distintos sociólogos que han

salido a “explicar” situaciones de pobreza, niveles de ingreso e

índices Gini diversos como supuestas “causas” del la instalación del

caos, es evidente que se trata de un problema de (falta absoluta de)

dirección política de la sociedad y no de un problema “social”.

Argentina está ante una crisis de gobernabilidad en toda la línea.

El

Gobernador de la Provincia de Córdoba, José Manuel de la Sota,

connotado anti-kirchnerista, y ejemplo mismo de peronista irredimible,

declaraba sin rubor alguno: “(Era)

impensable para cualquier gobernante que esta reclamación salarial (de

la policía) derivara en esta situación que se vive en las provincias.

(…) Se rompió el contrato social”.

La

declaración es inaudita porque presupone, o bien que la Policía,

sistemáticamente mal paga, hubiese roto un contrato social del que el

peronismo fuese un sabio guardián. O, peor aún, permite leer la

posibilidad de que los saqueadores hubiese “roto el contrato social”

cuando toda la Argentina sabe dos cosas fundamentales. La primera, que

los saqueos, como bien dijo al presidenta (que conoce bien el mecanismo

porque es experta en la materia), fueron como siempre organizados por

las organizaciones de base y los “punteros” peronistas de nivel

barrial. Y la segunda es que de la Sota finge ignorar que, de 1945

hasta la fecha, el peronismo y las Fuerzas Armadas han atacado

sistemáticamente todo intento de mantener nada parecido a un contrato

social estable.

El

gran violador del contrato social en la República Argentina es, hoy,

un gobierno peronista que, en la mejor tradición de Juan Domingo Perón,

ignora lo que debería ser el Estado de Derecho. El gobierno

kirchnerista persigue a los periodistas, pretende manipular medios de

prensa, intenta expropiar a los sectores de productores rurales, saquea

empresas nacionales y extranjeras, pretende “inventar” los precios de

la economía mintiendo abiertamente en las cifras macro-económicas, etc.

por lo que hace muchas décadas que la sociedad argentina y los simples

ciudadanos saben que viven más en una situación casi hobbesiana que en

una sociedad regida por algo parecido a un contrato social. Y decimos

“casi” porque, en Hobbes, la hipótesis que abona al “estado de

naturaleza”, supone una “guerra de todos contra todos” donde los

contendientes son hombres “iguales por naturaleza” los que se

enfrentan. En la Argentina, en cambio, los grandes agresores y

transgresores de la paz cívica y social han sido históricamente los

gobiernos peronistas y los gobiernos militares que se ensañan, desde

siempre, sobre la población.

Por

ello es que no deben de sorprender a nadie, en el mundo lejano que no

conoce a la “Argentina profunda”, las declaraciones de una saqueadora

de iniciales E.G. publicadas por “El País” de Madrid:

“La

mayoría roba, pero uno va a saquear para dar de comer a los chiquitos.

Cuando vas a decir al intendente (alcalde) que no tenés para comer, te

dice que no tiene nada más que una bolsa con un paquete de fideos, uno

de arroz, uno de azúcar, uno de puré de tomate y una botella de aceite

por mes, pero te dura dos días”, se queja. E. G. se entera de la

organización de saqueos por el boca a boca y Facebook, aunque hace una

semana se le descompuso el ordenador. En 2012 fue a saquear porque su

marido solo tenía trabajo un día por semana, ganaba 90 euros al mes y

con otros 155 de subvención estatal su familia comía una vez por día.

“No tenía miedo porque fui con mi papá”, cuenta. Ahora su marido

consiguió empleo formal, cobra 790 euros, sus hijos han vuelto a comer

dos veces por día, pero ella planeaba saquear porque la carne vacuna y

el pan “aumentan mucho” de precio. Aclara que otros vecinos roban

electrodomésticos o ropa para después revenderlos y

comprar después bienes básicos. También están los que no participan de

saqueos por razones morales o por el riesgo de resultar heridos.

Esta vez la presencia de gendarmes la disuadió de ir. “Ni loca voy a

que me maten”, cuenta y reconoce que delincuentes y policías de civil

participan también de saqueos mientras que punteros (dirigentes políticos barriales) los promueven.” (Edición Internacional del 11/12/2013).

Poco

queda que agregar a las declaraciones de esta “ciudadana”. La

espontaneidad de su amoralidad la exime de cualquier comentario. ¿Qué

de censurable hay en el saqueo y el robo si ella ha visto multiplicarse

de manera exponencial en pocos años el patrimonio de la pareja

Nestor/Cristina, si toda la población comenta cotidianamente los

negociados del vice-presidente Amado Boudou, si la clase política

peronista es el centro de corrupción de la sociedad argentina y si la

policía también es parte del esquema general de corrupción, para no

nombrar mas que los casos más notorios ?

Mientras

que el debilitamiento de la gobernabilidad se hace cada vez más

notorio en el país, los personajes de la política peronista intentar

encontrar la forma de sacar réditos del desastre. “Las influencias de

la dictadura” o “las corporaciones” son ahora el nuevo “tema” que han

desenterrado los auto-llamados “intelectuales peronistas” integrantes

de un movimiento llamado “Carta Abierta”. Y mientras estos personajes

juegan a ser políticos, la República de China eleva un tanto el tono

exigiendo que el gobierno garantice la seguridad de los inmigrantes

chinos afincados en Argentina. El gesto es meramente protocolar porque

la China sabe, perfectamente, que el gobierno de la Argentina es

absolutamente incapaz de ofrecer garantías, o seguridad, en tema

alguno.

|

How far should a journalist go to secure access to a violent or repressive country? This question grabbed the attention of academics earlier this year after the BBC used a group of London School of Economics students to disguise a visit to North Korea to film undercover for a Panorama documentary.

Local researchers continue to use research to challenge policies. They may not march down Kigali’s streets, but they are far from ineffectualStraus’ views are widespread among researchers on Rwanda. Soon after the publication of Remaking Rwanda, I attended a US State Department briefing at which the majority of the 20 assembled experts on the country said that they had not been there for several years – some since the late 1990s – because they were either officially personae non gratae or believed they would personally be at risk if they returned. One well-known academic told the meeting that it was not possible to conduct fieldwork in Rwanda unless one toed the line on all aspects of government policy.