'It's getting worse': China's liberal academics fear growing censorship

Professors are being banished from the classroom apparently for

subscribing to ‘mistaken ways of thinking’, as Xi Jinping shatters hopes

of political reform

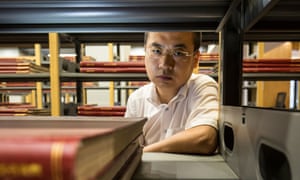

It has been a year since Qiao Mu last set foot in the classroom; a

year since officials banished the outspoken journalism professor to the

library of the Beijing university where he had taught for more than a

decade.

“They didn’t give me any reason,” said Qiao, who believes the move

was a form of punishment for his support of ideas such as multi-party

democracy and freedom of speech.

Unable to teach, he spends his days writing English summaries of

textbooks and daydreaming of running for a Chinese parliament in free

elections. “My colleagues and I believe that in maybe 10 or 15 years China will begin democratisation,” he said. “In 15 years I’ll be 60 – it’s still a good age for a politician.”

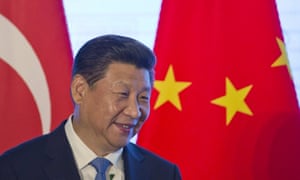

As Xi Jinping

approaches the end of his third year as head of the Communist party,

Qiao’s political aspirations appear more fanciful by the day.

When Xi came to power in November 2012,

some Chinese liberals hoped he might bring some measure of political

reform. Foreign observers noted his father was believed to have opposed

the 1989 military crackdown in Tiananmen Square and that his daughter was studying at Harvard University. Yet those hopes have proved spectacularly misplaced.

Xi – a leader so powerful one academic calls him “the chairman of everything” – has instead presided over one of the most severe crackdowns on opponents of the Communist party in decades.

Activists say at least 232 people have been detained

or interrogated since early July as part of an offensive apparently

intended to silence human rights lawyers who have criticised Beijing.

Liberal academics such as Qiao – an associate professor at the

Beijing Foreign Studies University – have also felt the pinch and

complain of growing censorship and intolerance of their ideas.

“It is getting worse,” said Qiao, 45, whose public advocacy of

western-style democracy and civil rights made him a thorn in the

government’s side. “Since [Xi] came to power the government has placed

tighter controls on ideological research and education. It’s like a

minor cultural revolution.”

The plight of China’s universities remains a far cry from the

excesses of the Mao era. Notoriously hostile to the notion of higher

education, Mao once told a Communist party colleague: “Knowledge is not

acquired in schools.”

Hundreds of institutions were shuttered altogether during the

cultural revolution as Mao’s red guards ran riot, with intellectuals

persecuted or exiled to rural labour camps.

But the clampdown under Xi still represents a disheartening turn

for those who had hoped a period of greater relaxation was on the

horizon. “I haven’t seen it so bad since the 1980s,” said Tim Cheek, a

historian from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver who is an

expert on Chinese intellectual life.

Cheek said liberal Chinese academics were now facing the most

pressure since western ideas and practices were attacked by the

anti-spiritual pollution and anti-bourgeois liberalisation campaigns of

the 1980s.

“I didn’t see it coming and I don’t think many of us did. I thought

the party would become more latitudinarian and more flaccid [under Xi].

But this is a real muscle-up to grandpa’s way,” said Cheek.

“[Liberal academics] are very depressed. They see no way of stopping

the logic and the direction of what Xi Jinping is doing because he is

shutting down civil society – or putting very strong constraints on it –

and they are hunkering down. They feel that what we are seeing now is

what we are going to get for the next 10 years, which just stuns me.

They think this is a long-term situation.”

Such academics were “collateral damage in a much bigger political

struggle” through which Xi Jinping was attempting to reinvent and

strengthen the party in order to save it from collapse, Cheek added.

Through his Communist party “counter-reformation” the president was now

demanding absolute obedience from his followers and purging those seen

as obstacles, he said, adding: “The loyalty he is demanding of

intellectuals he is already demanding, much more harshly, of party

members.”

Chen Hongguo, a former law professor at the Northwest University of

Politics and Law in Xi’an, traced the chill back to early 2013 when an

internal Communist party communique called Document Number 9 began to circulate.

The confidential directive warned that for the party to retain power,

seven “mistaken ways of thinking” needed countering – including human

rights, judicial independence and multi-party democracy.

At a stroke such ideas were outlawed in the classroom, said Chen, who resigned from

his position in December 2013 citing an increasing lack of academic

“freedom, openness and tolerance”. “If a university lecturer is not

allowed to discuss these concepts in class, what can he teach?” he said.

Qiao said that since Xi came to power the stakes had risen

dramatically for liberal thinkers who used social media such as Weibo – a

Chinese microblogging site similar to Twitter – to spread their ideas.

“Before Xi Jinping we feared only that they would delete our posts.

In the worst situation they would delete your [account],” said the

academic, who joined his university in 2002. “But since Xi Jinping came

to power this changed. They began to arrest people.”

Facing rising pressure, some are looking to escape.

Academics

from two leading western universities said they had noticed an uptick

in the number of mainland scholars looking for temporary academic roles

and suspected some were looking to distance themselves from Xi’s China.

Others have already left. Xia Yeliang, an outspoken economics professor, moved to the US in January last year after Peking University sacked him for what he claims were politically motivated reasons.

“I miss my friends, my relatives, my parents – so many things,” said

Xia, who is now a visiting fellow at the Cato Institute in Washington.

He claimed a nationwide smear campaign that saw state media label him

incompetent and “anti-party” had made him unemployable in his own

country. “I was forced to leave. There was not a single university in

China who dared to accept me as a faculty member.”

Cheek admitted not all academic topics of discussion would have been

affected by the tightening under Xi. “You can talk about the exchange

rate of the renminbi [or] you can bemoan corruption at the local level

... and that is not a problem,” he said. “It doesn’t threaten the party

order.”

However, any scholar whose work irritated or threatened the party was

now likely to face “heat”. Cheek said many liberals were “going into

campaign mode which is to keep your head down, keep out of the way,

don’t let stuff get into writing”.

“We are all trying to figure out what it means,” he added. “The bad

news is it is getting worse. There’s more supervision. There is more

pressure. The good news is that my Chinese colleagues respond in a way

that they have for decades, which is: they cope and they dissemble and

they bide their time and they phrase things in another way. So I don’t

see them giving up.“

Chen Hongguo said the Xi era had had a “chilling effect” on Chinese academia:

scholars were self-censoring or completely avoiding certain topics

while many journals now shunned potentially controversial issues

altogether.

Still, he was upbeat. “It’s impossible to silence the intellectuals,”

Chen said. “I’m not a blind optimist, but the trend [of society

becoming increasingly liberal] is irreversible.”

Qiao played down his period of confinement to the university library.

“It’s not a big punishment. It’s not like Nelson Mandela,” he said.

He said he was determined to avoid being driven into exile so he

would be prepared to run for office when democracy eventually came to

China.

“I have studied the transition of eastern European countries –

usually it is professors, writers, lawyers and journalists who become

politicians,” Qiao said. “I want to be a congressman – to criticise, to

supervise the corrupt government”. “We must change our nation, not our nationality.”