La trama oculta

Audio inédito del fiscal Nisman: “Aunque quieras matarme o sacarme del medio, esto ya no tiene retroceso”

28.02.2017

BUENOS AIRES (Uypress) — Pasados dos años de la muerte del fiscal de la causa AMIA, Alberto Nisman, se conoció un impactante audio que aparecerá en el libro “Memorándum”, del periodista Daniel Berliner.

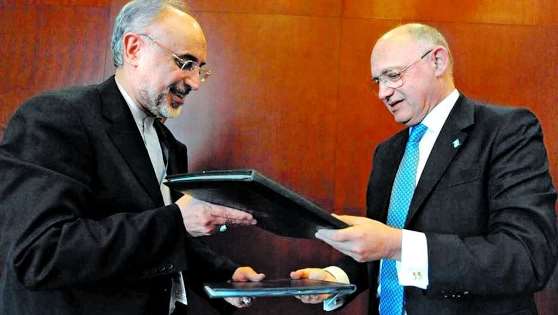

(El excanciller argentino Héctor Timerman con su par iraní Alí Akbar Salehi)

Dos años han transcurrido desde la

muerte del fiscal Alberto Nisman, y su deceso y las causas siguen

envueltos en la nebulosa y rodeados de las más variadas especulaciones.

Nisman investigaba el atentado a la AMIA

registrado en 1994, que dejara un saldo de 85 muertos y centenas de

heridos, y el memorándum de entendimiento firmado entre el Gobierno de

Cristina Kirchner y su par iraní. El fiscal se aprestaba a presentar el

19 de enero de 2015 una denuncia penal contra la Presidenta y su

canciller, Héctor Timerman. Un día antes, el domingo 18, fue encontrado

muerto en su apartamento, en circunstancias aún no esclarecidas del

todo.

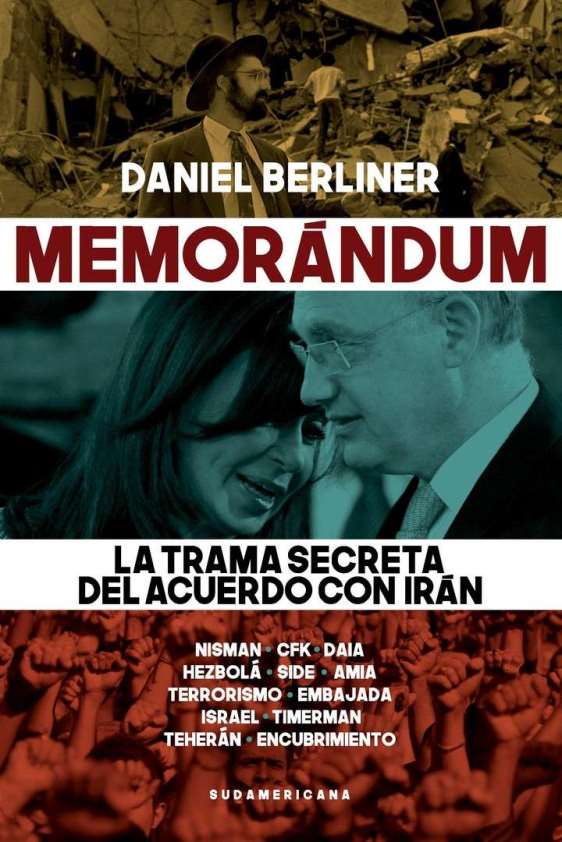

Justamente "Memorándum" es el título del libro que presentará el periodista de la Agencia Judía de Noticias, Daniel Berliner.

De acuerdo a un adelanto brindado por Clarín,

"Memorándum", el libro de Berliner, revela pasajes desconocidos de las

negociaciones del gobierno de Cristina Kirchner con Teherán, y reproduce

diálogos inéditos con el fiscal Alberto Nisman poco antes de su muerte.

También, entrevistas con diplomáticos y líderes israelíes, como

Benjamín Netanyahu y el ex canciller Avigdor Liberman y con funcionarios

del gobierno argentino.

El autor recrea las presiones, los

enojos, las vacilaciones y los desencuentros que provocó en la comunidad

judía la noticia de la firma del acuerdo.

En el capítulo final se reproduce esa conversación

clave de Berliner con el fiscal Nisman, quien aparecería muerto cuatro

días después de denunciar a Cristina, al ex canciller Héctor Timerman y a

otros, por encubrir a través de ese pacto a ciudadanos iraníes acusados

por el ataque a la AMIA.

Aquí, sus tramos salientes, adelantados por Clarín.

"Aunque quieran sacarme del medio"

(Tapa del libro de Daniel Berliner)

(Tapa del libro de Daniel Berliner)

- Alberto Nisman: Daniel, esto es un

espanto, es una aberración jurídica, inaplicable, es lamentable, es todo

una gran mentira. [En el Memorándum] se habla de fecha del viaje cuando

en realidad, más allá de que no conduce a nadie y que es completamente

inconstitucional, para viajar, según lo que dice ese mamotreto, tiene

[que haber] una comisión de la verdad. Para eso tenés que conformarla,

la tenés que integrar, tenés que evaluar.

Mirá, lo más suave que yo voy a tener

para decir, más allá de no entrar en la parte delictiva, es que tanto

Cristina como Timerman no se han cansado de mentir. No [es] que han

dicho una o dos mentiras, no se han cansado de mentir. Tengo quince

escritas, cada una de ellas verificable, y ahora hay que escuchar al

señor canciller decir, encima: "Vamos a tratar de que todos los puntos

se puedan cumplir". O sea, firmamos algo hace un año que es un espanto y

encima te dicen: "Vamos a tratar de que se pueda cumplir".

Evidentemente, es todo un mensaje para la gilada, se siguen cagando de

risa [de] los familiares, de todo. Fue un espanto esa reunión, te lo

dicen los propios tipos argentinos, está difícil porque tienen la contra

allá [en Irán] y sacaron esto para salir del paso, o sea, esto, aun en

el caso de que conduzca a algo, es inconstitucional, pero encima estás

pagando el precio de un Mercedes, no por un Mercedes [sino por] por un

auto fundido, no es más que una vergüenza más que va a saltar a la luz

en poco tiempo.

(...) AN: Que esto quede entre nosotros:

esto termina, y cada vez en menos tiempo, con gente presa, y mirá de

qué manera te lo voy a decir, no es [por las] pruebas que tenga el

fiscal, que igual serán muy válidas, porque es un fiscal al que en nueve

años jamás le han revocado una resolución, nadie. ¿Qué decís vos si yo

te digo que acá hay involucrados funcionarios del Estado, y la prueba me

la otorga el mismo Estado?

- Daniel Berliner: No se puede digerir fácilmente.

(...) AN: Con todo esto el Gobierno no

está haciendo más que corroborar y darme más elementos con la teoría que

ya se está armando, de lo cual sobra prueba. Que sigan igual, que sigan

igual, vas a ver cómo termina todo esto. Yo antes decía que esto

termina mal en un año; ahora te digo, es cuestión de meses.

(...) ¿Sabés cuál es la diferencia? Yo

lo pensé desde el primer día, la diferencia es que yo tengo las pruebas y

con la pruebas más de uno que ni se imagina le va a temblar el orto,

porque no es prueba inventada por mí, no son valoraciones (que son

totalmente válidas), no, no, cuando vean las pruebas proporcionadas por

el propio Estado (porque, obviamente, hay internas en el gobierno), te

agarrás la cabeza, Daniel. Esperá, esperá un poco, seguí con tu laburo y

todo, pero yo te digo: el ejemplo es feo, lo voy a dar, porque hablar

de bombas, de esquirlas y todo en el contexto de lo que pasó es feo,

pero acá hay que alejarse (los que están vinculados con todo esto) lo

antes posible para que no le pegue alguna esquirla a pobre gente que

quizá no tiene mucho que ver al lado de los máximos responsables. Ahora,

que los máximos responsables terminan presos en poco tiempo, no tengas

duda.

Y si a esta altura hablo por esta radio

[Nextel] ya en estos términos es por dos motivos: hay mucha gente que

respalda la prueba que hay, y, fundamentalmente, la prueba está guardada

de tal manera que, aunque quieras matarme o sacarme del medio, esto ya

no tiene retroceso. Algunos embrujados ya lo saben y no saben cómo salir

y están pidiendo salvavidas, así que, que me escuchen. Ya no sé si

puedo hacerlo público, si alguno me está escuchando, a esta altura me

chupa un huevo, porque cada uno sabe lo que hizo, lo que dijo y dónde

quedó registrado, así que el problema lo tienen ellos, no yo, y va a ser

muy cómico cuando se demuestre y uno diga, entre otras cosas, la frase:

"Y decían que no querían que esta causa sea una pieza de ajedrez del

tablero geopolítico internacional". Vamos a ver ahora quién usa esta

causa como un tablero de ajedrez, si un fiscal que solamente trae las

pruebas o justamente el gobierno que quería acusar al fiscal diciendo

que seguía lo que quería Estados Unidos, veamos lo que aparece acá.

(...) DB: ¿Estás tranquilo?

- AN: Más que tranquilo. Yo estoy

absolutamente tranquilo, los que no tienen que estar tranquilos, porque

yo considero que todavía estoy viviendo en un país normal, son los que

hicieron estas cosas.

(...) Ya no te hablo como fiscal, estoy indignado, avergonzado, asqueado con ganas de vomitar muchas cosas.

- DB: ¿Entonces Eliaschev se quedó corto?

- AN: Mirá lo que te voy a decir, y vos

sabés que yo lo critiqué: Eliaschev se quedó corto, no en lo que dijo,

en lo que leyó, porque él en definitiva reproduce, y lo saca de unos

documentos que dice haber leído. Se quedó corto, corto, corto, corto. Lo

que dijo es verdad, pero se quedó corto. No lo estoy criticando, lo que

te quiero decir es: imaginate la gravedad del tema.

- AN: Pero... ¿qué "recibir"?, ¿sos

boludo? Lo van a tener que ir a visitar a Devoto en pocos meses. A ver

si me entendés lo que te digo, ¿de qué "recibir" me estás hablando? Van a

tener que pedir turno en la cárcel. La lógica indica que deben saber

muchas más cosas que yo, con lo cual la situación sería desesperante.

[Timerman] es un maleducado, un grosero,

un guarango, vaya a saber lo que le habrá dicho [a la embajadora

Dorit]. Yo la tenía como una mina de bolas, [pero si] está en otro país,

tampoco se puede hacer la loca. Tampoco la Cancillería israelí está

jugando un papel fuerte en esto, más allá de lo que piensen y de que no

lo reciban; son los más blandos de todos estos también. En su momento,

cuando tenga la oportunidad, se los voy a decir: "Flojo papel público de

la Cancillería israelí, y esto no es nuevo". Muy tranqui, los conozco a

todos, los fui a visitar. Hay que poner las bolas sobre la mesa.

¡Comparame la Cancillería israelí con Netanyahu!, es vergonzoso lo de la

Cancillería israelí.

Bueno, Daniel, te mando un abrazo, esto fue entre vos y yo y los que están escuchando."

UyPress - Agencia Uruguaya de Noticias